Mostly garlanded by images poached from Winter Is Coming, Bitches. Also, *spoiler alert*. And now subject to discussion in a critical post by Charli Carpenter over at Duck Of Minerva.

At first sight, Game Of Thrones offers something rather different to the standard fantasy fare. Where Lord Of The Rings and its ilk deal in arch dialogue and grand quests, it provides a more gritty and twisted landscape, peopled with dwarves, bastards, spoilt brats, noblewomen who still breast-feed their near-pubescent sons, eunuchs, exiled criminals and incestuous twins. In one conversation, Baelish and Varys even discuss a Lord who enjoys sex with beautiful cadavers (fresh ones only). A fantasy not only of palaces and mystical objects, but also of the gutter.

At first sight, Game Of Thrones offers something rather different to the standard fantasy fare. Where Lord Of The Rings and its ilk deal in arch dialogue and grand quests, it provides a more gritty and twisted landscape, peopled with dwarves, bastards, spoilt brats, noblewomen who still breast-feed their near-pubescent sons, eunuchs, exiled criminals and incestuous twins. In one conversation, Baelish and Varys even discuss a Lord who enjoys sex with beautiful cadavers (fresh ones only). A fantasy not only of palaces and mystical objects, but also of the gutter.

There is a near-scandalous thrill to this aesthetic realism, especially when measured alongside the allegoral formality of The Chronicles Of Narnia or the cinematic marathons derived from Tolkien’s high Toryism. Where those source materials and corporate cinema required that sexuality be wrapped in chaste folds and circumvented as the higher union of pure love, Game Of Thrones can indulge lust, rutting and the explicit mention of rape. There’s even talk of homosexuality (although not for any of the linchpin characters with whom we are expected to identify). Bared breasts are the order of the day. Childhood tales filtered by HBO.

But this apparent radicality doesn’t go very deep, and in significant ways covers for a narrative saturated with race-thought and misogyny. How so? Some decades ago Michael Moorcock wrote of Tolkien as a coddling lullaby:

The Lord of the Rings is much more deep-rooted in its infantilism than a good many of the more obviously juvenile books it influenced. It is Winnie-the-Pooh posing as an epic. If the Shire is a suburban garden, Sauron and his henchmen are that old bourgeois bugaboo, the Mob – mindless football supporters throwing their beer-bottles over the fence, the worst aspects of modern urban society represented as the whole by a fearful, backward-yearning class for whom “good taste” is synonymous with “restraint” (pastel colours, murmured protest) and “civilized” behaviour means “conventional behaviour in all circumstances”. This is not to deny that courageous characters are found in The Lord of the Rings, or a willingness to fight Evil (never really defined), but somehow those courageous characters take on the aspect of retired colonels at last driven to write a letter to The Times and we are not sure – because Tolkien cannot really bring himself to get close to his proles and their satanic leaders – if Sauron and Co. are quite as evil as we’re told. After all, anyone who hates hobbits can’t be all bad.

This critique focused heavily on Tolkien’s antipathy to all things modern and his construction of villainy as co-extensive with industrialisation and heroism as the soothing hierarchies of village life (a contrast many have sought to read in terms of Fascist modernity versus steadfast English conservatism). This peculiarly English inflection does not mark Game Of Thrones, but reactionary echoes persist in the narrative force given to civilisation/barbarism, to some familiar gender boundaries, and to blood lineage as the organising category of political association.

Take the Dothraki. Tribal, nomadic and tattooed, they lack the resourcefulness to innovate any particular devices of their own and show little capacity for abstract thought or cultural invention. Governed by brute custom, they fear the sea and can only understand the very concept of a ship via metaphors of wooden horses that cross the water. Their basic mode of sexual encounter is rape, and they prefer to do it from behind, like animals. In political terms, they grasp obedience and social organisation in relation to strength (demonstrated through physical violence) but not honour or duty. A Khal does not need the cunning to distribute resources or buy alliances: there is nothing to distribute for such people, who have no apparent habits of trade and acquire possessions only via conquest. Pre-capitalist savages, the Dothraki are so starved of even moral exchange that they have no words for ‘thank you’. Seriously. Their language has the harsh intonations familiar from other racialised constructions, like Klingons without technology. Oh, and they’re quite swarthy.

Take the Dothraki. Tribal, nomadic and tattooed, they lack the resourcefulness to innovate any particular devices of their own and show little capacity for abstract thought or cultural invention. Governed by brute custom, they fear the sea and can only understand the very concept of a ship via metaphors of wooden horses that cross the water. Their basic mode of sexual encounter is rape, and they prefer to do it from behind, like animals. In political terms, they grasp obedience and social organisation in relation to strength (demonstrated through physical violence) but not honour or duty. A Khal does not need the cunning to distribute resources or buy alliances: there is nothing to distribute for such people, who have no apparent habits of trade and acquire possessions only via conquest. Pre-capitalist savages, the Dothraki are so starved of even moral exchange that they have no words for ‘thank you’. Seriously. Their language has the harsh intonations familiar from other racialised constructions, like Klingons without technology. Oh, and they’re quite swarthy.

Khal Drogo rises above this mire somewhat, charmed by the bedroom manoeuvres of Daenerys Targaryen, who has some advantages as the only figure with the touch required to bring forth dragons. Married off to Drogo as the bargaining chip for his army, it is she who becomes the sock-poppet for a Game Of Thrones version of feminism. Wilful in spite of her relative fragility, Daenerys derives her determination from the male heir inside her – ‘the Stallion that mounts the world’ (natch) – until she trades his life so that Drogo may live on in a vegetative state. Empowered by protective feminine impulses over her precious boy cargo, she transcends the pliant object we first encounter to become a commander of men, but only so long as she can claim to speak for their true Lord (wait until I tell Drogo about this!)

In a parody of anti-rape politics, it requires the authority of this high-born Queen to prevent the conquering Dothraki army from sexually violating the wives, mothers and daughters of the conquered. ‘Freeing’ the women by effectively making them her personal slaves, Daenerys puts her trust in a witch among them and is repaid for her naive kindness when said sorceress infects Drogo, leading in quick succession to a mutiny by the Dothraki, the still birth of her child and the death-cum-zombification of Drogo. Having thus taken us through the tropes of woman as canny seductress, shrill matriarch, over-emotional ingénue and diabolic fate, Daenerys enters the fire and emerges reborn as vengeful harpy, naked save for a small host of dragons. A monstrous feminine.

Which brings us to gender politics. The most common female figure is that of the whore; the most common male one a loyal killer. Physically weak, generically meek, hopelessly devoted to their menfolk, the women of Westeros cower and sob at violence and prove useless at the calculations of politics. Catelyn Stark provokes outright war by bowing to her maternal urges and kidnapping Tyrion Lannister on slim evidence that he tried to kill her son, a decision unlikely to have been endorsed had she consulted with her husband, notorious as he is for bad decisions. Cersei Lannister, as Queen of the realm, fares better, managing to manoeuvre her son onto the throne, at which point he becomes a power-mad sociopath, forcing Tywin Lannister to send his own imp son to the capital to pick up the pieces and rule from behind the scenes. Which leaves Arya Stark, everyone’s favourite tomboy, protected from the solid binaries of Man and Woman by the relatively ungendered space of girlness. Thin and still flat-chested, she is able to pass, Shakespeare-like, as a boy. For now.

Which brings us to gender politics. The most common female figure is that of the whore; the most common male one a loyal killer. Physically weak, generically meek, hopelessly devoted to their menfolk, the women of Westeros cower and sob at violence and prove useless at the calculations of politics. Catelyn Stark provokes outright war by bowing to her maternal urges and kidnapping Tyrion Lannister on slim evidence that he tried to kill her son, a decision unlikely to have been endorsed had she consulted with her husband, notorious as he is for bad decisions. Cersei Lannister, as Queen of the realm, fares better, managing to manoeuvre her son onto the throne, at which point he becomes a power-mad sociopath, forcing Tywin Lannister to send his own imp son to the capital to pick up the pieces and rule from behind the scenes. Which leaves Arya Stark, everyone’s favourite tomboy, protected from the solid binaries of Man and Woman by the relatively ungendered space of girlness. Thin and still flat-chested, she is able to pass, Shakespeare-like, as a boy. For now.

But what of state and nation? Westeros is divided into Houses and Realms, geopolitically marked with particular kinds of traits and characteristics. The Lannisters are rich and arrogant (their sigil the Lion); the Starks a winter people, hardened and sultry sullen (their sigil the Wolf); and so on. A core narrative strand involves Ned Stark attempting to put a universally-acknowledged brute on the throne in place of Prince Joffrey because his is the true blood and hence the rightful succession. Although the various Houses host bastard sons and incompetent siblings in a somewhat higher proportion than more coddling fantasies, the propulsive dynamic is the same: how to win power for the right high-born son. Since the good/bad continuum in Game Of Thrones works primarily in terms of benevolent rulers versus maniacal ones the only political theory needed is that which will help choose between competing Kings.

There are two standard responses to these kind of criticisms: that it’s only a story and that these tropes only reflect reality (either because their portrayal of difference is true or because their portrayal of attitudes to purported difference is true). It’s arguable to what extend any representational strategies impact on applied cognition and behaviour. But fiction is an important stage for ideas about war, diplomacy, sex and race, not least because we’re freed to engage in a more fulsome emotional investment precisely because it’s not real. Excepting professional researchers, activists and inveterate news addicts, the time spent with such representations outstrips that devoted to engaging them in the realm of contemporary politics. Moreover, fantastical motifs don’t stand apart from more prosaic ones, despite their setting. They layer and map onto the ideas of appropriate social organisation that we bring with us, and they do so in fairly obvious ways.

More damningly, this is fantasy. It’s very conditions stipulate possibility and world-making. So why do the worlds so often echo and telegraph stereotyped copies of our own histories rather than their alternatives and subversions? This is the crux of Moorcock’s critique of Tolkien and others, that they indulge regressive ideals in the name of ‘escapism’, so that even in lands of ghouls and dragons the same parameters of race, sex and nation apply. There is nothing special about the content of fantastic or the speculative when it comes to hierarchical imagination. But its form too easily convinces that the critiques which apply to, say, Sex & The City, lose their relevance in crossing the boundary of genre.

More damningly, this is fantasy. It’s very conditions stipulate possibility and world-making. So why do the worlds so often echo and telegraph stereotyped copies of our own histories rather than their alternatives and subversions? This is the crux of Moorcock’s critique of Tolkien and others, that they indulge regressive ideals in the name of ‘escapism’, so that even in lands of ghouls and dragons the same parameters of race, sex and nation apply. There is nothing special about the content of fantastic or the speculative when it comes to hierarchical imagination. But its form too easily convinces that the critiques which apply to, say, Sex & The City, lose their relevance in crossing the boundary of genre.

Forcing the complex of characters, plot twists, witty quips and possible readings into the above framework will seem to do some violence to the overall experience. Worse, it will implicate the critic as sourpuss and over-thinking killjoy. But enjoying Game Of Thrones (and I very much did) doesn’t contradict these points. Enjoyment is the point. Emotional identification is what gives tropes their power, and is what makes cultural critique all the more relevant for the aesthetic objects of our affection. Otherwise there is but the empty posturing of a high culture echo chamber. Mel Gibson’s depiction of Christ is anti-Semitic. Oh, really? A clean and costless denunciation. Somewhat harder to examine the kinds of fantastical connections we make and the kinds of imagined subjectivities we’re being asked to identify with.

On which note, a parting gift for the Sansa Haters:

A completely wonderfully written and wide-ranging article that seems to have failed to grasp the essentially infantile nature of fantasy itself. Never truly creative, our fantasies are almost always backwards looking, stuck and stale, substituting – as they do – retread and fetshising for new experience and growth. But a lovely read, nevertheless.

LikeLike

Critical compliment are definitely the way to go round our way. That said, I think this is a fundamental contest, one I didn’t highlight enough, between the role of non-realist fiction as infantilism and as critical rethinking. Fantasy hasn’t got a great reputation for the latter, and I agree that the problems you cite affect fantasy far more than, say, speculative fiction/science fiction, but it’s not a universal rule.

Take Ursula K. Le Guin, Neil Gaiman or Michael Moorcock himself. In all three cases, motifs common to the fantasy genre (knights, medievalesque settings, dragons, wizards, etc.) are deployed to quite different ends, whether in eschewing a focus on the daily travails of nobles, recasting gender rules or merely playing with and subverting standard expectations. ‘Speculation’ as a catch-all term for this kind of invention can certainly be creative, critical and even liberatory in intent. But those sorts of fictions likely don’t conform well to what many expect from their fantasy, even when it is on HBO.

LikeLike

That may be true about a particular strain of fantasy, but good fantasy is myth-making that like historical myths, produces and examines cultural values.

Plus this comment is particularly ironic in the face of Martin’s actual work, which is in large part a direct subversion of classic, “infantile,” nostalgic fantasy.

LikeLike

Writing from Mordor (what? okay. you want REAL names. Pittsburgh. Otherwise known as “hell with the top taken off”).

Martin plays with our expectations… it’s not the knights who are worthy (Ned is no KNIGHT), but the dwarves and bastards. He subverts the Shakespearean, as he flows with it (Robert’s bulk aptly depicts his kingdom rotting).

But read Kulthea, if you want an awesome world.

I don’t see the Dothraki the way you do. They are a nomadic people, whose trade and barter comes more with stories than trade goods. Hence Drogo’s chant.

And I don’t believe for one second that Dany gains agency because of her belly.

LikeLike

Ned may not be a knight, but he is a Lord, a nobleman with a lineage and a territory, and also Hand of the King, which rather trumps mere knighthood in terms of mediavelesque hierarchy.

On the Dothraki, there are several characters who act as our introduction to Dothraki ways and speak in expositionary mode at crucial points. Nothing we see as viewers contradict these statements. So it is claimed that the Dothraki have no concept of loyalty and only respect strength, and so it proves when Drogo ‘dies’. We see them as inveterate rapists, and this is repeatedly confirmed by conflicts between Dothraki foot-soldiers and Dany.

I don’t think her agency comes *only* from her belly, but that doesn’t necessarily make things less problematic. For example, what makes us identify with her is her struggle to find some agency in the most misogynistic context showed in the series. But when she does so, it still seems to me to be via a series of standard patriarchal tropes, whether that’s because she’s Drogo’s wife, because she carries his male heir, or because she is herself descended from a great male king and/or is somehow linked to a plane of being beyond regular mortal constraints (there be dragons there!).

I should also clarify that my comments are aimed at the HBO series, not the books (which I haven’t read). My sense is that the series is fairly faithful, but I’ve seen enough wonders of speculation tarnished (Dune: The Miniseries anyone?) to be suitably wary.

LikeLike

The thing is that she’s been raised in a deeply misogynistic culture and married into a different deeply misogynistic culture. She can’t just force her way through as modern woman by herself and survive the attempt.

The reason for these patriarchal tropes is that they function as a pressure release valve, allowing those women who can’t remain in the system to break outside it without destroying the whole. As she has several possible just-so stories (her son, her husband, being of the blood of kings, etc.) to justify her eccentricity, she has no reason to try and blow up the entire gender system. She is bought off and the Dothraki system survives to put far more women in their place.

LikeLike

This is really wonderful– you have articulated all the main points I’ve had swirling in my head as I’ve watched Game of Thrones… except one. To my mind the Dothraki– at least as portrayed in the series, I have not read the books so I have no basis for comparison–are a melange of explicitly Orientalist stereotypes. The “nomadic/horse” elements of their culture are clearly Native references– but even as Native Americans were misidentified as “Indians” in real life, so are the Dothraki thinly veiled offensive Arab/Berber analogues, papered over with decorative “Native” symbolism. I agree wholeheartedly with the specifics of your analysis–including the creepy gender politics of Dany’s story. But even her role as the blond, “civilized” pseudo-European Leader “gone native” is an Orientalist trope from The Sheik to Lawrence of Arabia. That this role is filled by a woman is not a feminist innovation, but rather the integration of its female analogue–the pale, virginal white-slave, harem girl: a two-for-the-price-of-one Orientalist scenario. This becomes especially clear in contrast with the Witch who embodies the equal and opposite stereotype cluster for actual Arab women: seductive, magical, sympathetic in her sexual exploitation… but ultimately treacherous. While the rest of the Dothraki and their slave/prisoners are portrayed by everyone from actual native, African descended actors to brunette Europeans the Witch–“Mirri Maz Duur”– is clearly Arab in her accent and character presentation. The fact that the pretty blond rose triumphantly naked from ashes that contained her cremains should be acknowledged. Even among feminine “monsters” the white girl’s life comes at the expense of a character described as a heavyset, flat-nosed woman with black hair.” Right.

I suppose I need to write about this myself in further detail but i couldn’t resist chiming in to your fascinating post.

Best,

Joe

LikeLike

Thanks Joe. Do chime in!

I completely agree with your analysis, and you set out the Orientalist dimension better than I do with my nod to language and skin colour. I don’t think there’s much feminist about Dany’s role, and the phrase ‘sock puppet’ was supposed to reflect that I can see some attempting a feminist defence of the apparently ‘strong’ female characters. Because some of them don’t cower and even appear to lead. This empowerment is ultimately illusory, and the strength that exists is by way of associations with men – as their wives, daughters or mothers. That of course reflects the historical reality of many kinship systems – east and west, as it were – but that only takes us back to the question of why this is the fantasy.

LikeLike

It’s not the fantasy. A very large part of the series was a response to the Fantasy portrayal of medieval systems. GRRM has a quote somewhere about how the feisty peasant girl could never tell off the handsome prince and get away with it. He’d rape her for her insolence, then have her executed or placed in the stocks. The fantasy authors adopt the trappings of medieval society but fail to grasp the cultural dynamics within that system.

This isn’t to defend GRRM from making some very poor decisions in his portrayals of people and cultures, but a large part of what you’re decrying is intended to be decried.

LikeLike

I don’t about arab connection, but mirri is a jewish and an Israeli name.

the black hair and the accent also relate to Israeli people

LikeLike

I agree absolutely with your concluding paragraphs – they’re the missing layer I’ve been waiting to read on a fair few blogposts on GoT.

Particularly your point here: There are two standard responses to these kind of criticisms: that it’s only a story and that these tropes only reflect reality (either because their portrayal of difference is true or because their portrayal of attitudes to purported difference is true). It’s arguable to what extend any representational strategies impact on applied cognition and behaviour. But fiction is an important stage for tropes of war, diplomacy, sex and race, not least because we’re freed to engage in a more fulsome emotional investment precisely because it’s not real.

A lot of responses to GoT seem to have gotten stuck on those two standard responses and then just sort of circled for a bit, and I think you lay the issues out very eloquently.

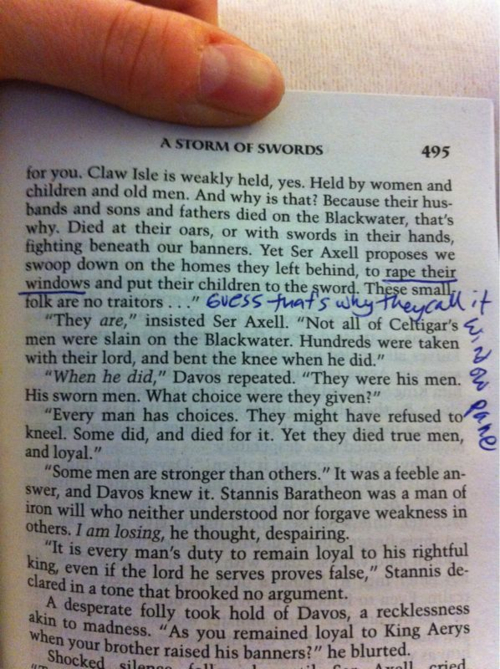

Oh, and that windows typo is something else!

This post rocks, and I’m regretting not netting it exclusively for BadRep! Do call for tea with us soon, though – you’re very welcome 🙂

LikeLike

Cheers Miranda… Next time! Also, if you’ve read some other good stuff, drop us a few links. I only read something else on it after I wrote (keep the mind uncluttered etc.) and am eager to take the pulse of the internet.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Duck of Minerva: Friday Nerd Blogging: IR Feminism(s) in Game … | Profittable Blogging Secrets

“the Starks a winter people, hardened and sultry”

This word, I do not think it means what you think it means.

Nit-picking aside, I find it hard to respond to this post without bringing in knowledge gained from reading the books and knowing what happens subsequently. (Possibly a spoiler) For example, in the books, Mirri Maz Duur does not ‘poison’ Drogo (and the TV show itself is ambiguous on this point); she makes him a poultice, which he removes because it ‘itches’. He turns to Dothraki remedies and the wound then becomes life-threatening.

As for why GRRM (or ‘Gurm’ as he is sometimes known) chose to make Westeros such a brutal place… well. I think it is a large part of the series’ strength. Gurm is happy for good things to happen to bad people and vice versa; in LotR and its many clones, evil gets its comeuppance. People (well, ‘good’ people) die nobly and for worthwhile causes. ASoIaF isn’t like that, and is very refreshing as a result. Gurm has a real knack for creating believable and rounded characters who change significantly over the course of the books. As a fantasy fan, it is marvellous to read a series where the nobly-minded, fair and handsome are no safer than anyone else; in fact, their honour is a weak point. The grimdark world of Westeros brings this quality of the story to the fore.

Bah. I am a fan, so have a fan’s desire to ignore the aspects of the story which make me uncomfortable. You raise interesting points, in any case. Although I take exception to the “most common female figure is that of the whore” bit; even counting background characters who don’t speak, I don’t think that can be said to be accurate. Dany’s handmaidens aren’t whores; the women at court in King’s Landing are not either, nor are the various Septas, Old Nan and so on, to say nothing of Arya, Sansa, Cersei, Catelyn, Mirri Maz Duur, and Lysa.

LikeLike

Quite right on ‘sultry’, although the more expansive definition including it as a more human adjective does capture some of the passionate intensity I detect in House Stark. I think I mean sullen.

A number of objections have been raised here and on Twitter to the question of fidelity to the books. I understand the reaction, and share it, fan-boy that I am, in many contexts. However, I think it is primarily problematic when judgement is being passed on an author or their intentions on the basis of a derived piece of work. That’s not what I’m doing here, and I don’t think it’s necessary to preserve this kind of fidelity. Game Of Thrones as book and as series are separate cultural products and although the audiences will clearly overlap, they shouldn’t be expected to match each other, or for criticisms of one to be answerable in terms of the ‘true’ intentions latent in the other.

It’s entirely legitimate to discuss the plot and character of ‘Fight Club’ without talking about Chuck Palahniuk. If someone wants to criticise him for the ending, of course, I’d expect them to know that it was different in the book. But without some preservation of relative autonomy between the different ‘versions’ you end up with an infinite regress. After all, Gurm doesn’t paint on an empty canvas, but is building on, elaborating, and perhaps undermining, a set of existent fantasy elements and forms. It would be no answer to criticisms of his full oeuvre that you can only *really* understand it if you’ve read The Silmarillion.

A final point on being a fan. I tried to stress that it’s not about lecturing people on how *awful* the politics of their favourite books are. I’m not about to burn my Philip K. Dick collection because the female characters are a bit one-dimensional, and I still intend to read everything Anthony Burgess ever wrote, despite the passages in which he can’t help injecting his pathetic colonial imaginary into my consciousness. I think enjoyment and critique can co-exist, although there’s clearly an interesting tension.

LikeLike

I disagree that the gender politics of GoT are as uniformly retrograde as you’ve portrayed them. (I think you’re right about race.) I’ve been enjoying it much along the lines of Deadwood — the female characters appear stereotypical at first (whore, widow) but by the series end have become complex and central to the series. (Caveat: I’ve read the first book all the way through, but only seen a few of the HBO episodes.)

Consider: Daenerys has gone from being a passive object of trade to a warlord with an outcast army, with her objection to rape central to her process of taking power. I’m not sure why this is a “parody of anti-rape politics,” unless you think that battlefield rape has nothing to do with the desires of military leaders, nor am I sure her adopting rape victims as slaves is anything other than a complex response from a figure with real, but limited power. Her story looks poised to be the “fantasy” you’re talking about in your response to Joe: she moves from being empowered by men to leading them.

Catelyn’s first real “play” is seizing Tyrion. It’s a clever tactical move with disastrous consequences, gendered insofar as it’s payback for the attempt on her son Bran. As a tactical error it’s directly mirrored in the Lannister clan’s military response–I think it’s easier to hang it on honor’s inseparability from family than on sentimental, womanly vice. And by the end of the series, she’s essentially become Robb’s strongest field advisor. Negotiating passage across the Twins with various family pledges including betrothals may be a “feminine” action at some level but it’s hardly stereotypical.

I think you’re right that Arya, as a fightin’ tomboy, is neither particularly redeeming nor implicating. Which leaves Sansa, the most egregiously feminine character, whose love of heraldry blinds her to Joffrey’s whackadoo evil and her father’s peril. I think Sansa’s journey is an ideological critique of crippling femininity, and I hope that the beginning of her disillusionment atop the tower is the start of a strong arc from her. Though I don’t know what will happen.

LikeLike

To reiterate, you can have strong and central female characters whilst still deploying misogynistic tropes. The question is how and why they have these roles.

In the case of Dany, I maintain that she only ‘leads’ when she is acting as Drogo’s representative. Perhaps she will lead again now that she has harnessed the power of dragons, but I think this introduces an entirely new element, since she can hardly be claimed to be a figure for women in general at this stage. On the contrary, she is an *exception* to the normal rules (who else can commune with dragons?) and so takes on an almost supernatural aspect (I’d make a comparison with the way Jean Grey becomes Phoenix here).

And we’ll just have to disagree on Catelyn. It was always obvious that kidnapping Tyrion would trigger a major incident. And of course, it wasn’t Tyrion who tried to kill Bran, so her acute intelligence rather failed her there too. What was the result of her ‘tactical move’? The death of her husband, the placement of a sworn enemy’s son on the throne of Westeros (although that might have happened anyway), war resulting in the deaths of many hundreds, if not thousands, a brutal and degrading life for one daughter and an uncertain fate for another. Oh and the death of many loyal household retainers. A clever move this is not. Also, she’s far from Robb’s ‘field adviser’. She gives no advice on strategy. She provides the feminine justification for his revenge desires (a totally standard patriarchal role for women in times of war) and negotiates a crossing for him (because she is better placed as a woman to soothe the temper of a dirty old man).

LikeLike

Examine it from her perspective: her childhood friend, who was so devoted to her he fought a duel that would have been to the death for her hand, just swore that this man tried to murder her son. She’s trying to be incognito so that the Lannisters have no idea she’s onto them. Then suddenly he arrives on his way back to his brother and sister, and will tell them he saw her there.

She’s now terrified that the jig is up and they’ll move to tie up more loose ends, possibly by killing her husband and children in King’s Landing. Add to this her maternal instincts and the fact that he’s in a place where she has more power than him (due to their being in her father’s lands) and it does make some sense. It’s not wise, upon reflection, but this is a split-second decision, and less idiotic than it seems.

LikeLike

I don’t disagree with the race issues. Beyond offensive, they’re lazy, obvious and silly. I’m not sure whether they reflect the books, since I haven’t read them, but since most fantasy and sci fi basically borrow from the real world’s eurocentric pathologies and paradigmatic histories, it’s not surprising to find, time after time, that our heroes are white people with names like Robert speaking in a generic British accent, and that our villains tend to be shirtless, dark-skinned, sexually voracious people who need an interpreter to communicate with real people.

Beyond that, I think the series deserves some credit for daring the viewers to view those white heroes in a historically accurate way; as rapists, murderers and power drunk fools. The dialogue between the witch and demyris is notable for being absent of any affectations or signals to the viewer that we should consider the witch evil or her act villainous. There’s really not much to disagree with there from her point of view, and yet the series dares us to take the side of the true villain, Demyris, a child of privilege who was quite willing to be queen for her brutal husband, whom she loved despite what would be considered today a mass murdering psychopathic personality. The truth is that our canon has been asking us to side with such brutal murder for hundreds of years, making it comfortable for us to do so by affecting the weak in the equation with bad habits, and nasty dispositions. The game changer here is that the program asks you to examine your own idea of who the hero is in a very unique way that I think shouldn’t be tossed aside so casually.

LikeLike

Well, I prefer to think that I tossed it aside with a degree of deliberation and thought. After all, I didn’t say that there were no interesting gender moments in GoT, only that they weren’t nearly as radical as some seem to think, and that they were counter-acted by a very heavy dose of regressive and reactionary tropes.

I’ll agree that Mirri Maz Duur unsettles our idea of Dany somewhat in that scene, making us see her as a bit naive in her hope that rescuing the women would be appreciated by them, but this is at least in part because Duur is too caught up in her ritualised existence to appreciate a life outside of custom. Leaving aside the racialising implications of such a position, what I don’t think is possible in Game of Thrones is for Mirri Maz Duur to become a heroine herself. She advanced the story by the poison-death-zombie storyline, but was then burned out of existence. That this kind of role for the Arab-ish witch can be seen as a ‘game changer’ in depictions of race and gender rather seems to me to bolster my point.

LikeLike

Well, yes, but my argument isn’t that such characters as Mirri can become heroes. It’s that they would be the heroes in a rational story line. But it’s the villain that is given the narrative spotlight, with all the vanities of character and nuance that come with it, including survival. It has the potential to leave the viewer feeling a bit awkward because to enjoy the story they still have to side with Demyris, who’s the obvious villain. I still think it has the capacity to leave the viewer thinking a bit harder than they usually would if the Arabish character was treated with the narrative disdain usually reserved for them in these kinds of stories. Maybe they’ll look at the story of the American revolution a bit differently next time.

LikeLike

I have nothing to say– except OMG, I love this post. I never warmed to Tolkien, GRRMartin or CSLewis, though I tried very hard because if you’re a fantasy fan, they’re supposed to be read (one of those things about fitting in), still can’t really decide what one likes unless ones reads a few. I settled with being a UKL fan, and I absolutely love her male characters.

Have you seen this?

http://shakespearessister.blogspot.com/2011/04/game-of-thrones_18.html

LikeLike

Cheers R,

UKL (that’s Ursula K LeGuin to the rest of you) is the go-to author for demolishing the idea that fantastical narratives have to be regressive by definition. I think I read the Wizard of Earthsea books before Tolkien actually, which might have something to do with that. She also comes out very well in Moorcock’s ‘Epic Pooh’ piece and shows how the genres can mix (‘The Left Hand of Darkness’ is both fantasy and sci-fi for those interested in the purity of genre lineage).

LikeLike

Awesome, thanks I’m going go read the essay now.

LikeLike

“More damningly, this is fantasy. It’s very conditions stipulate possibility and world-making. So why do the worlds so often echo and telegraph stereotyped copies of our own histories rather than their alternatives and subversions? This is the crux of Moorcock’s critique of Tolkien and others, that they indulge regressive ideals in the name of ‘escapism’, so that even in lands of ghouls and dragons the same parameters of race, sex and nation apply. There is nothing special about the content of fantastic or the speculative when it comes to hierarchical imagination.”

This a thousand times! I have the same issues with certain fantasy series but can never put it quite so eloquently and succinctly. I don’t know much about GoT, I saw one episode and was bothered by the same old power-hungry mother/sassy whore/princesses in need of protection tropes not to mention the depiction of the few darker skinned people. I came away frustrated (again) that a fantasy series has seemingly relied so much on history/reality and exhausted stereotypes.

It’s difficult to navigate the waters of criticizing such a popular and beloved series while still emphasizing your enjoyment but you did a really great job of that here. Excellent post!

LikeLike

You claim that GoT ought to have constructed a more modern female identity, but I don’t think you understand the purpose of GoT. GoT isn’t escapism so much as it’s Martin’s slap to the face of the genre, sending a shock through our systems.

Martin’s Thrones is a journey through the worst ugliness of the human condition especially in how that ugliness burns to ashes and ravages the fantasy tropes that came before. I believe that his inspiration comes from focusing on all the terrible moments in history that are so often forgotten by historians and ESPECIALLY by fantasy writers.

Martin puts our noses to the dung and forces us to breath deep.

I won’t defend his portrayal of the Dothraki. He failed to make them 3-dimensional as a society. I agree with the charge of Orientalism there.

But as for the anti-feminism? Martin shoves the worst ugliness of the patriarchy down our throats and he forces us to taste it.

I applaud him for that.

LikeLike

Hi Brian,

Thanks, but not quite. As I mention several times, I’m not interested in indicting Martin so much as examining how Game Of Thrones was presented as a TV series. Moments of slaughter and savagery enacted by bad guys who look darker than the good guys aren’t rare moments in fantasy: they’re it’s bread and butter, as you seem to accept.

As for the anti-feminism, what I suggested instead was that the series showed a thin version of feminism. This isn’t the same thing. As for shoving patriarchy down our throats and making us taste it, maybe, but that would rather depend on us not enjoying it and identifying with it as the series does so. Perhaps your claim is that the series encourages no positive association with heroic male leads who protect the womenfolk, and that there is no sense in which we are encouraged to either pity or despise the central female characters. But I don’t buy it.

Here’s the point you propose re-formulated: if what really attracts us to Game Of Thrones is the harsh encounter with the reality of patriarchy, why aren’t all those fans just reading histories of misogyny and feminist theory? What is it that requires dramatisation, and more than that, the posing of these various patriarchal scenarios in the form of fantasy?

LikeLike

*Cringes* did your Jewish professor teach you this half-baked Freudo-Marxian critical theory nonsense at sociology class, Mr Kirby? Oh, an employee of the London School of Economics, say no more. No real man can type the word “mysognist” with the intent of an epithet without sounding like a total poofter.

LikeLike

Anti-semitism, homophobia *and* anti-intellectualism! Quite a feat in three sentences.

I have no idea whether my sociology teacher is Jewish, although he was more of a Simmel-Benjamin fan, if that figures in your sub-Breivikian lexicon (OH NOES! HERE COME THE CULTURAL MARXISTS TO DILUTE OUR MALE VIRILITY!).

As for failing your carefully-calibrated masculinity test, I guess I’ll just have to sniff away the tears and find a way to muddle through.

Also, it’s “misogynist”.

LikeLike

Thanks a ton for applying free time in order to compose “Race,

Gender and Nation in �Game Of Thrones� (2011) � The Disorder Of Things”.

Thank you once again -Bessie

LikeLike

“Race, Gender and Nation in �Game Of Thrones� (2011) | The Disorder Of Things” staticcaravansforsale was indeed a remarkable blog post.

If it included alot more pix it would likely be perhaps even better.

Cya ,Genevieve

LikeLike

Pingback: Tom Holland on ‘A Game of Thrones’ | Chaos and Governance

I totally agree! Fantasy and sci-fi both really lack true original premise…game of thrones is based off hamletish, shakespearean characters.

LikeLike

Good day! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before

but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new

to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking

back frequently!

LikeLike

Pingback: Game of Thrones as Theory (via Foreign Affairs) | Misanthrope-ster

Pingback: 2011 Futures Game Selections | Increaseinformation

Pingback: Should we care about Gender Prejudices in Game of Thrones? | Elleanor Wears

Pingback: Unit 12 – Media Investigation – Finlay thompson's Media